Extra Extra!! From the banks of the Reese River, a newspaper that propped up a honest-to-goodness LIARS CLUB, no lie, and a story from the city who built itself on such falsehoods. The secret history of bitcoin? The Toiyabe Mole Man in the mines of ERN, NEVADA? The TRUE story of TOTAL LIARS and the history they invented for themselves, and for us.A story about lies, hoaxes, squibs and narrative foundations poured directly on top of rock-hard truth in some places, yet in others, onto the shaky ground of an earth pocked with tunnels and holes.

| • | • |

The word “Bitcoin” comes from an old mining phrase.

Silver was discovered in Nevada around the 1850s, and out-of-work miners in the spent claims of California rushed back the way they came, building cities in the high desert mountains. These towns would boom in just weeks, thanks in part due to coordinated promotion. A salesman would be hired by landowners or mine owners to travel around the west and convince people that his town was the next big thing.

Frequently these promoters would never see their marks again, and so… they’d lie through their teeth. The more people they convinced to move to their city, the more money they made, and the easier it was to convince other people to do the same. The phrase those promoters would use to attract people, was the phrase “Bit Coin.”

As in, “Ladies and Gentlemen, we officially *Bit Coin* in Silver City. You oughtta get there as quick as possible if you wanna bite some coin yourself!”

One day in 1862 a promoter showed up in Virginia City, claiming coin had been bitten in Central Nevada. It was an isolated stretch of desert mountains, and on the edge of the apparent vein was a newly-founded city called ((ERN)). At the time Virginia City was booming. And though the flush times were good for some, a lot of the workers got there late and couldn’t even afford a place to live, sleeping in tents and lean-tos and dusty bedrolls on the periphery of town. Some heard about ERN from the promoters on C Street or read about it in the Territorial Enterprise and thought ‘that might just be a way to get in on the ground floor’. These hopeful souls pulled up literal stakes, and rode horses and mules to a place that would become the geographic center of Nevada. and when they got there, they killed and ate the horses they rode in on.

Though they had not seen the promised veins of silver, feet thick, easy pickings, they had faith in this new place, and value—above all—was in faith.

What they didn’t know, is that nobody in ERN had really bitten coin. Not much anyway. There was a little silver here and there, but the promoters successfully blew it out of proportion to bring people to the town and to sell land and building materials and absinthe and shaving cream and jeans and newspapers. And so the city of ERN flourished. Like many boom and bust mining towns, the population grew quick. A newly built board building in the dirt-road down town soon became home to a newly founded newspaper to serve the curious readers settling on the sagebrush steppes; this was The Reese River Reveille.

The Reese River Reveille, named for a nearby waterway, would soon become world famous for a column dutifully penned by editor-in-chief Fred H Hart, and that column was called the Sazerac Lying Club.

At the time, there was frankly no expectation for objective, information-based reporting, and that kind of practice—the factchecking and clear attribution and careful parsing of words and obliteration of doubt from behind a bushy mustache that they teach in Journalism school—that would not take root until the mid 20th century. Back then, there were often multiple papers in a single small town, and readers would choose the one whose editorial bent or sense of humor aligned most with their own, so they could read mostly real news through the lens of a trusted eye.

The Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City for instance, where Samuel Clemens became Mark Twain, was a paper where tall tales and exaggeration were part of the DNA. Its readers knew as much, except for when they didn’t, and the exaggerated missives of a possibly lubricated journalist landed as claims of hard bitten truth. Twain was even apparently run out of town over an ill-recieved squib.

The papers were frequently staffed by a bohemian crew of literary misfits who had tried their own hand at mining, but fell back on their pens when it became clear that the only people making money in the mines were those who already had a lot of both. Now the The Reese River Reveille in ERN, Nevada existed squarely in this context, and was known to push the boundaries of metallic reality. The paper spent its first couple of years as a town promoter itself, reporting generously on the rapid growth of the new mining operations, and drumming up hype.

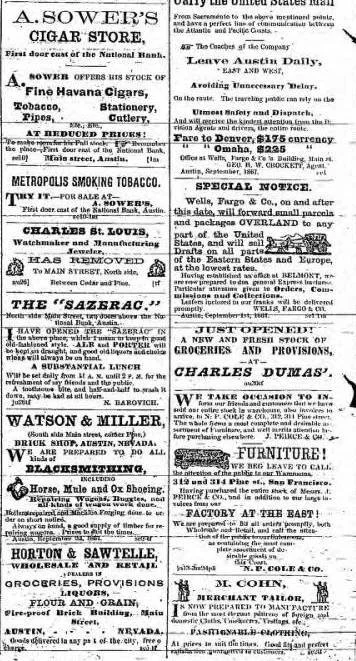

Neighboring papers would routinely call each others claims into question and the Reveille was often the can on a post.

"A Gentleman just in from the Reese River informs us that the ledges there which are called a foot thick are generally from one to two inches… What a lying age we live in.” -The Gold Hill NewsAnother paper from Reno wrote,

“To bite coin is a phrase fitting of Gold, not silver, for Gold is soft enough to bend under teeth. Silver, however, is harder and a bite of a silver coin does not reveal its truth.” -The Reno Theoretical CrescentDespite, or perhaps because of its loose and fast approach, a lot of Nevada, even outside ERN subscribed to the Reveille. And with that readership, ads sold fast. Advertisements took up more than two thirds of the pages at one point. Event listings for dances, personals taken out by prostitutes, one man even advertised his own life - claiming that he so desperately needed the money, that whoever paid the highest price would be allowed to shoot and kill him.

What started as a lie in the newspaper, slowly became reality. The Sazerac Lying Club began to organize.

Even though they were initially upset with Fred Hart for making the whole thing up, the club adopted the name, the man Hart called George Washington Fibley became the actual presidentThe club would meet up in the evening, and Fred Hart claimed he’d pan through the stream of tall tales to deliver the nuggets of story-telling gold to readers of the Reveille.

Illustration by M Jiang, 2018

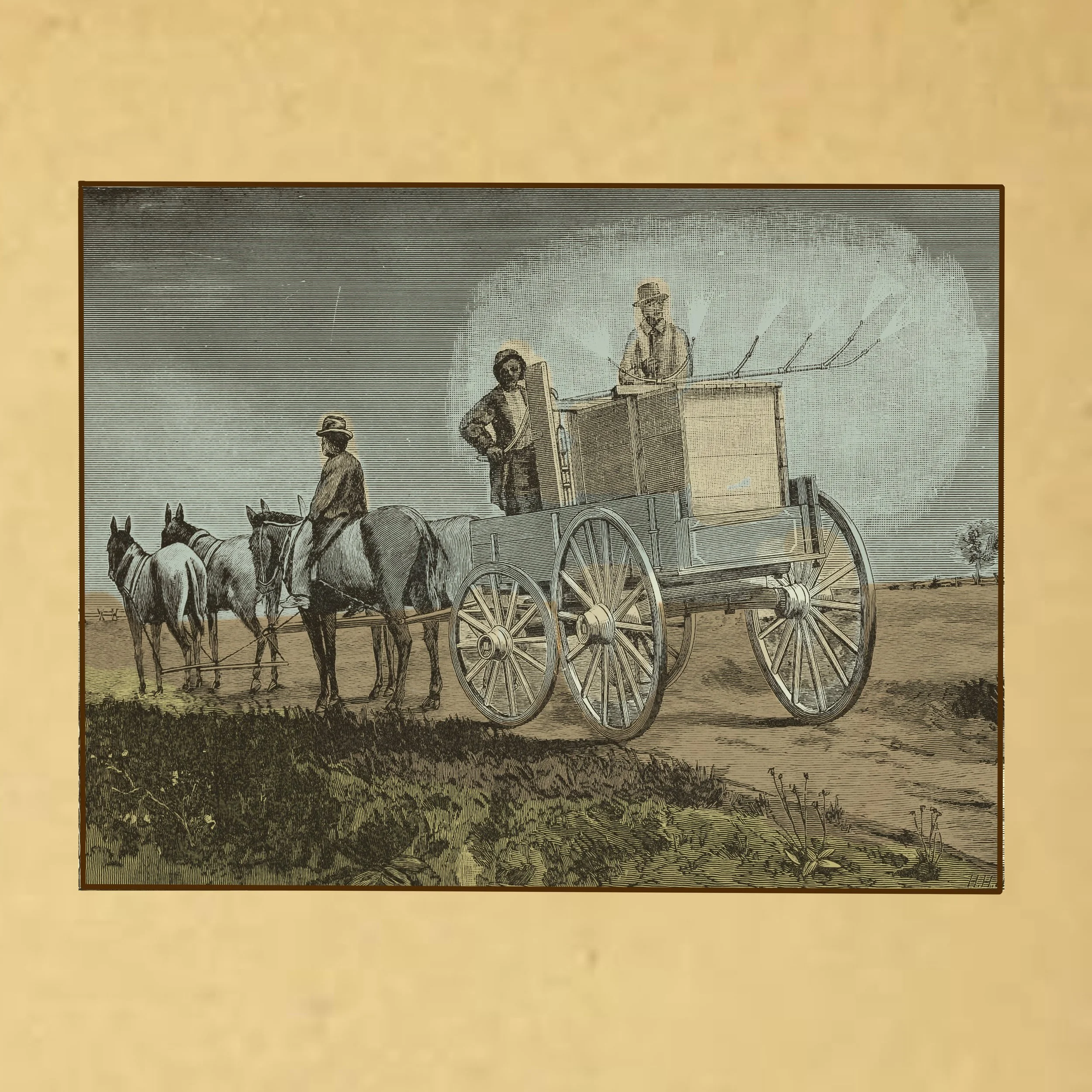

One popular story is this one: A Liar named Uncle John was riding up the highway south of town and saw a low, dark cloud blocking the road. At first, he thought it was a freak storm which is not uncommon in the high desert, but he got closer and realized it was not a storm but it was birds. Thousands of birds. He tried to ride through, but when the horses on his wagon hit the wall of birds, it felt as if they had run into a brick wall. The wall stretched across the entire valley, so he turned back and headed up to visit a friend who he knew had blasting dynamite for mining. They figured if they could tunnel through the earth, they could tunnel through the birds. But after a long ride back to the road, telling his friend about the incredible sight he was about to see, there wasn’t a single bird in the valley. This, he explained, was why he was late to the meeting.

That story was reprinted, as they often were, a few weeks later this time in a German paper, BUT the translation strayed. In the German version, the man returned with his friend and they blasted a hole with the dynamite and tunneled through the bird cloud, which had been changed to geese and in this version, presumably, Uncle John was on time to the meeting. And that is how the story is remembered.

The column paints a colorful picture of the Club’s behind-the-scenes deliberation. In fact, it spends quite a bit of time talking about motions and applications for membership, social slights and head butting. Hart’s Club will argue and spit, pulling tight against the lies of their fellow members, calling bullshit, evaluating the merits not just on truth but on the way the thing unfolds. It’s interesting seeing the peer-review in real time, deciding what flies and what sinks, a de-mo-cratic process.

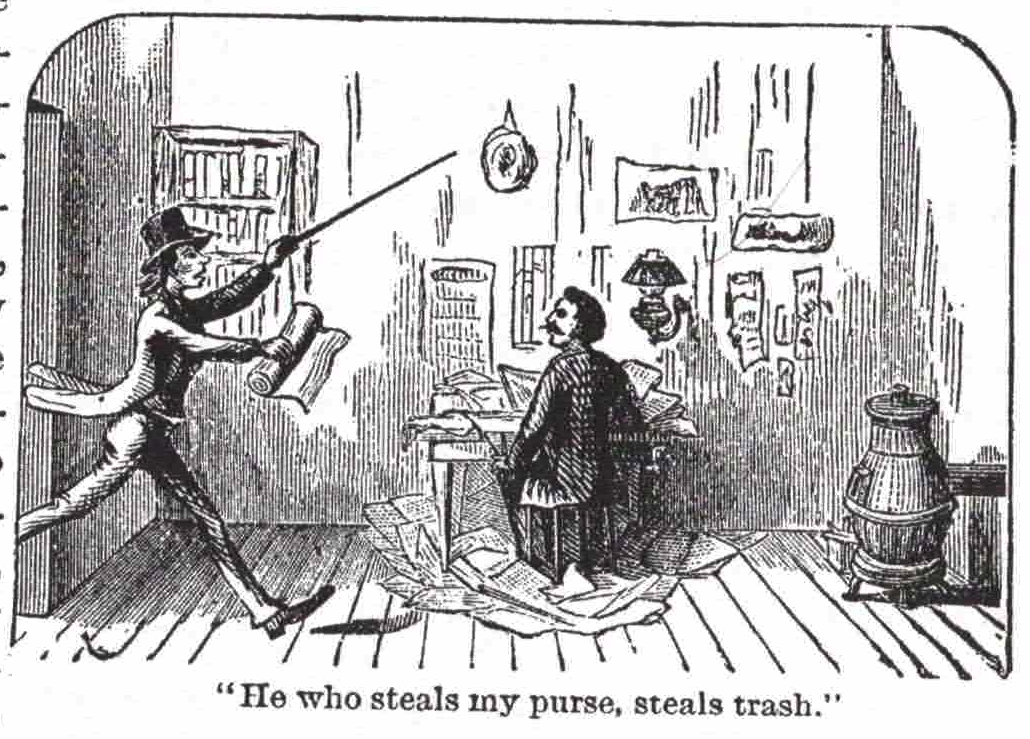

At one point a liar points to a picture of President George Washington on the wall and asks if the club knows the story about the cherry tree. The reply is tepid, so he recounts the founding tale: the boy’s receipt of an ax, his excitement to put it into use and the felling of his father’s favorite tree. When the dad returns, he heads straight to the slave’s quarters where he slathers blame on anyone near. But none of the men enslaved by the Washington family take responsibility, so the father searches for his kid who is now manically hacking away at an old board in the barn. Future president George Washington is caught dead-to-rights, and admits his mistake and falling to his knees, asks for forgiveness. His dad is so moved by this simple truth that he bursts into tears and accepts the apology in a beautiful moment of national pride.

“Wal as for me,” one liar says in response, “I think it’s the dog-gonedest biggest lie as was ever told in this here club and I’d like to hear the sentiments of the gentlemen here present on the subjeck.”

The group puts the story to a vote, an in unanimous decision, they deem it a downright LIE.

“Thus did the club,” Hart wrote, “in one fell blow, demolish a great truth of American History.”

As ERN reached it’s peak in the 1870s, the miners and townspeople could intuit that something was off. They could feel that the metal beneath the mountains was lighter than promised, not nearly enough to maintain the gravitational force it takes to anchor a city to the desert floor.

But before the bust, there was still money to be made. The men still sent promoters to parts unknown. Hell, if they could sell their homes and buildings and mining claims (salted or not) to newcomers and men of speculation, they might not get left holding the bag.

In this national market economy, speculators need not be prospectors either. Combing through far-flung newspaper reports and word from trusted scouts, investors from afar—San Francisco, New York—would buy shares into the mines and companies of frontier businessmen living shabbier lives than they, out on the edge of the economic fringes. Useful, to the men in suits.

Though some bought stake in specific mines, gambling on the assayer’s initial findings, other investors followed the credo that those who get rich are those who sell goods to the hopeful. Townspeople would offer shares in their construction companies, their saloons, their dynamite importation business. Some of these were bonafide, some just smoke in the shape of a man.

One savvy business owner knew that the suits on Wall Street were no fools, and that a smart man would know that heavy ore must be transported from the hinterlands to a real city where smart men could process it and tuck it safely into a trustworthy bank, or similar institution. And so he founded the Reese River Shipping Company which purported to lend transport of raw ore from ERN Nevada by Freight Ship up the Reese River all the way to San Francisco. The men in New York saw opportunity here; if the silver was as abundant as the Reveille seemed to believe, the men would be rich.

The details not included in the telegraph were as follows:

The Reese River is in the Great Basin and so never makes it anywhere near San Francisco, instead petering out in a local desert sink.Also

The Reese River is about a foot deep and in most places you can step across it without getting your boots wet.With these details lost to omission, the shipping company sold many shares.

Over the course of regular congregation, the Sazerac Lying Club adopted rules and bylaws. The most notable laid out in the columns of the Reveille was that professional liars like politicians would not be admitted, and that lies would not be malicious or self serving; they would only allow lies which amuse or elevate without harm.

Many of the stories are indeed victimless, and usually about mining, fishing, hard travel. But some were not at all harmless. Dozens include a protagonist who tricks, steal from or outright kills the non-white both in town and in the mythic places that the liars hailed from. The Paiute, Shoshone and Washo, joined by Black and Chinese folks were the target of outright smear campaigns, and sometimes their mere presence the entire punchline. One chapter in Hart’s book, which later compiled his Lying Club columns, is simply titled “Indians and Chinese” and it goes as one may imagine.

The stories unfold against a desert backdrop bigger than the average reader can envision. They also unfold against a violent process of killing, drilling and extracting everything possible from an unfamiliar landscape.

The Chinese Exclusion act, Slavery, bounties on the body parts of the indigenous, women’s subjugation, Manifest Destiny; all from a story people told themselves. The story of who we are, about why we weren’t getting rich, about where we, as a country, came from.

Lies were used to inflate the value of the town.

Lies were used to stratify every person in it.

Today ghost towns exist across the western deserts because natural resources are scarce. When the Silver or Gold dried up, it was no longer sustainable to transport food, water and lumber to town. So the residents would leave. What I’d like to say is that there was a lie so fantastic that it killed the town of ERN, leaving a ghostly husk in the desert wind.

Something like:

It’s around midnight and Uncle John leans in over the wood stove.

“Did you know this place is doomed?” he says, eyes darting to every tired face in the room. Wind whipping at the slats of the barroom.

“How would you know?” a liar mutters.

“Well”, John Says, “I was down in the mine and I heard a rustling at the end of the shaft. Knowing I should be the only one in there, I set my lantern down and crouched up against the wall, thinking whoever it was would assume I ran.”

“But the rustling got louder and louder, It didn’t sound like a person. It sounded like claws in the dirt, scratch scracth and they were getting real close. So I jumped up toward the lantern and pointed my gun into the darkness.

“Right then, a face stepped into the flickering light. It was a man, alright, but a man so gnarled, his skin was rougher than a bristlecone pine, and his limbs more crooked. His teeth were black as night, and his eyes were shut tight like they hadn’t been open in a decade.”

John shifts in his seat, the others leaning deep in to his story.

“And here’s what he says, he says, ‘your mountains ‘er runnin dry. Get on up to Bannock Montana where they bit coin last week,’ and finished the sentence with a resolute coughin’ fit. — And I think, he must be a blind promoter, maybe got turned around, came in here for shelter. But when he gets a breath he says

“I know what you’re thinking and I’m not a town promoter!

“I AM THE TOIYABE MOLE MAN and I can tell when a mine’s runnin dry from 12 miles away. And there ain’t no coin for 12 miles in any direction from where we’re standin’ right now.”

“I shook his grimy hand and walked back into town and right here into my seat in the Sazerac.

“So who of you wantsta go ta Bannock?” John finishes and the crowd erupts. Everyone in the bar believes every word which spreads like fire through the night, and they grab what they can and the town is deserted by daybreak.

But it wasn’t a lie that undid the town.It was the cold, hard truth.

The city could start up on hype and lies, but could only last so long. Eventually the mining operations that were promised to be bigger than the Comstock, weren’t. and the shipping companies that promised to transport silver never floated a single coin.

Today, ERN is practically a ghost town. The buildings still stand, the stone church, the heads of the mines, slatted walls meeting the high desert floor. A few bars here and there still function. The paper is long gone, just a patch of sagebrush in the breeze near the motel and gas station and the shut down hardware store with screeds taped to the windows.

The only thing that seems to be growing, new, is a large warehouse on the edge of town.

On the main street when asked a man in a flat-brim hat said it was a secret data center, just popped up, no one knows what’s in it.

An old timer ducking into the bar snapped his suspenders and rocked up on his toes saying “Bit Coin, my boy. It’s the Block Chain.”

And the lights stay on all night…

A few years into the Sazerac Lying Club, Fred H. Hart was offered a book deal. In the column he said the liars put it to a vote, and agreed to hand over the rights to their stories. However, they stipulated that all future lies and meetings would be private. The Reese River Reveille would stop printing their columns. And like that, the club publicly disappeared.

It is unknown whether the Sazerac Lying club dried up that night, flush with the royalties of a New York book deal. Or if they simply went underground for a while and then dried up along with the town, or if there are still some old miners in that bar today, sittin around, tellin’ lies.

« | • | »

Music by

2 Original songs by Emily Pratt. Emily makes music as Howls Road, support her work here:

And friend of the show Yclept Insan