Those Who Feast with the Mountain Lion

The story of a lithium mine in remote northern Nevada, and the two-spirit Paiute elder who fought to stop it.

For full story, listen to audio above. The following text are excerpts from the episode.

Dean Barlese: “I've gone to the other place and seen it. It's very beautiful.”

The path flowed like water

from the one place, to the next

and Dean Barlese walked it.

Dean Barlese: “So I've gone three times, I guess, in my hospital stays. And I've seen my mom, my dad, my grandmas standing there waiting for me. I'm walking up this little trail with green grass and flowers, sagebrush all around. You can hear the birds singing.”

And then, another time

there was a group out there

a group of protestors crouching in the sagebrush.

They were away from camp now, several paces off the ribbon of a dirt road that cut from the paved highway to a new chainlink fence. Behind the group, a teepee stood tall against the ridge — sage was waist-high as far as you could see, down into the valley, rippling to the next range in the east, purple and soft blue in the distance. The Nevada sun filtered through the hushed green leaves to reveal to them on the desert floor below: a nest.

Dean Barlese: “You had small birds in there that were just hatched. And the mother was trying to protect them.”

And then the group was back at their protest camp.

This was before the police came.

Dean Barlese. Photo by Max Wilbert.

Dean Barlese: “It made us feel good to stop construction, desecration of that place, sacred land, sacred ancestors that are still out there. It made us feel good. And we knew the ancestors were with us, by the little whirlwinds that came up through the road they had built. We knew we weren't alone.”

Not far from these little whirlwinds rising from the newly cut mine road, about 160 years south, a man named Fredrick West Lander met with the Paiute War Chief Numaga.

In 1860 Numaga had successfully defended his people with an incredible feat of military strategy. He lured a large group of war-bound vigilantes and miners and settlers hellbent on racial bloodshed into a canyon on the Truckee River near its terminus in Pyramid Lake, just upstream from Dean’s house.

The settlers rushed confidently, guns drawn, right into an ambush, and the Paiute warriors appeared in mass on a sandy ridge, then many more silently closed ranks behind them in a crescent, pinning the storming, ragtag brigade against the icy current, their clothes still wet and heavy from several nights of late spring snow. Their plans to exterminate the tribe once and for all were shot to pieces as many of the invaders lay dead in the sand.

When the few battered survivors returned to their newly established cities, Virginia, Carson, they enlisted a cavalry from California, who returned in force but only managed a stalemate with the tribe. The Paiutes retreated from their home on the lake.

They roamed the desert for a long time, as the United States Government waged war on their way of life, and built an overland wagon route through their homeland.

Fredrick West Lander was in charge of ensuring the safety of the wagon route and set up the meeting with War Chief Numaga. As custom, they sat silently for hours before speaking, Numaga studying Lander’s face and intentions until sundown, then a pipe was passed around and the meeting began.

According to an account compiled by author Ferol Egan, the two men spoke of past fights, settled accounts, tried to agree on the truth of things to varying degrees of success. Lander, on behalf of industry leaders and the federal government, then asked the Paiutes for safe passage through their land, heading toward the mining towns in western Nevada and over the great mountains to California.

“You have have big horn sheep and antelope ranges that the whites do not want.” Lander said, “You have lakes full of fish that the whites do not want.”

•••

A decade later, Numaga was dead of disease and a fort was built in those unwanted antelope ranges, and the Snake War unfolded as the Paiutes and Shoshone and Bannock wondered the steppes in retreat, and the military approached a camp at dawn and shot through the tent walls, killing everybody, entire families. And only 3 children survived.

Photo by Max Wilbert

A battery has 2 main polar parts: the cathode, the anode. Between them is a separator and a sort of fluid called an electrolyte. Lithium is a lightweight element that can be used in both the cathode and electrolyte solution. Basically, it holds a charge, and it can be reused over and over again. When the battery degrades, the lithium can be removed and reused without limit for the most part, assuming somebody is incentivized or required to recycle it.

There are other minerals that can do this too—hold a charge—sodium, magnesium, aluminum, vanadium…but lithium is lightweight, and already standard so momentum makes it the current mineral of choice. It’s also abundant. There are big deposits in Chile, Bolivia, Argentina, China, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, California…Here, the mine plans to use a water-intensive hydraulic mining process that will remove lithium-rich clay from the earth, then more water to process it into commercial grate lithium-carbonate.

Nevada is the driest state in the US, and the protesters and at least one nearby rancher believe that adding an industrial scale water user will decimate the meager water supply that is here.

This landscape has long been marked on the government maps as wasteland. Gold, silver, nuclear testing, data centers; the things they don’t want end up here, and the things they do want, flow out in big trucks.

And so the protesters stood in the road.

“We've always been here… Being two-spirited, or in our Paiute language, we say mu ka kwee tuhu uno a takadu (spelled phonetically)—Those who feast with the mountain lion. That is an ancient term for who we are, what we are, and in our old ways, we were created along with man and woman…a combination of both male and female. And we were the teachers, healers, caretakers of the knowledge, traditions that were passed on, stories…”

“We deal a lot, even in the old days, we had a lot to do with getting people ready for burial, dressing them up, wrapping them, doing the final prayers. So even today, once in a while, somebody asks me to come in and go into the mortuaries and dress the bodies, get them ready for burial…In the old days, we'd wrap the people up, take them out to burial. It's sad, but it's also a strong thing to do—to help people on their journey.“

Two Aeolian Harps used in this episode: Snake of Truth Wind Harp by Eleanor Qull and Obsidian Sky Wind Harp by Fil Corbitt + Mike Corbitt.

Thank you to Dean Barlese for trusting me with this story. Also a big thank you to BC Zahn Nahtzu (a co-defendant in the case, BC has an Etsy store here), Max Wilbert (a co-defendent who provided pictures), Olive Greenspan, Tara Tran, Ray Pang, Kate Cowie-Haskell, Taylor Wilson for talking to me about the chemical properties of Lithium and Daniel Rothberg for speaking about mining’s effect Great Basin water tables. Daniel has a newsletter called Western Water Notes which I highly recommend if you’re interested in that sort of thing. Also a shout out to the podcast Boomtown; a Uranium Story by Alec Cowan. Some of the books for this piece:

Sand in a Whirlwind by Ferol Egan

Legends of the Northern Paiute by Wewa and Gardner

Carpentaria by Alexis Wright

1491 by Charles C. Mann

Explusions by Saskia Sassen

Crow’s Range by David Beesley

Music from the Free Music Archive and Yclept Insan

Tags, Topics and Mentions: Peehee Mu'huh, Thacker Pass, Thacker Pass Lithium Mine, Ox Sam Camp, Ox Sam, Protect Thacker Pass, People of Red Mountain, Snake War, Fort Mcdermitt, Nevada, Lithium, Lithium Mining, Protest against lithium mine, Dean Barlese, Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation, Numaga, Pyramid Lake, Sand in a Whirlwind, Mountain Lion Harrah's Casino in Reno, Sagebrush, Mining, Lithium Carbonate, WinnemuccaThe Eviction Puppet Show of Silver Lake, Los Angeles

The sun sets over Sunset Boulevard; the palm trees silhouette. In the front garden of a big house off the main drag, the puppet show begins.

This is an audio-first story. For the full story, including the puppet show, listen to the podcast episode.

•

This is an audio-first story. For the full story, including the puppet show, listen to the podcast episode. •

The name of the house is Ag lago

Ag lago

“Ag lago.”

And it's in Silver Lake on Sunset Junction.

Sometimes I call it a punk house. Sometimes I just, I call it a collective house. Um, but... It's my home.Things go up on the property, but they don't often come down. So there's like literally decades of stories and projects and abandoned projects and ideas and evolutions that have just kind of built up over the years.

The basement is full of things that, of people who don't live here anymore, who lived here years ago. But besides that, there's a lot of like just things built into the house that were from people past, from cultures past.I didn't move in until 2008, so. Uh, by the time I moved in, it had a name, but when I first started coming here it didn't have a name yet, but, but that was pretty, pretty quick. It's pretty soon it got a name.

Ag lago

Ag lago.

•

We were in conversation with the landlord about getting our plumbing fixed. And so the last we had heard somebody was supposed to be out that week to fix our plumbing, and then …there was a demolition notice on the house.

When we decided we're going to stay and fight this eviction because we believed that we were being wrongfully evicted one of the things that I did was I started the GoFundMe for our legal expenses.

“Food Not Bombs is a mutual aid group that it's an autonomous group so anyone can start a Food Not Bombs chapter.”

And we cook a big meal and then just share it in downtown, yeah. At Skid Row.but the cooking has been happening for the LA chapter at Ag lago for like 20 years.

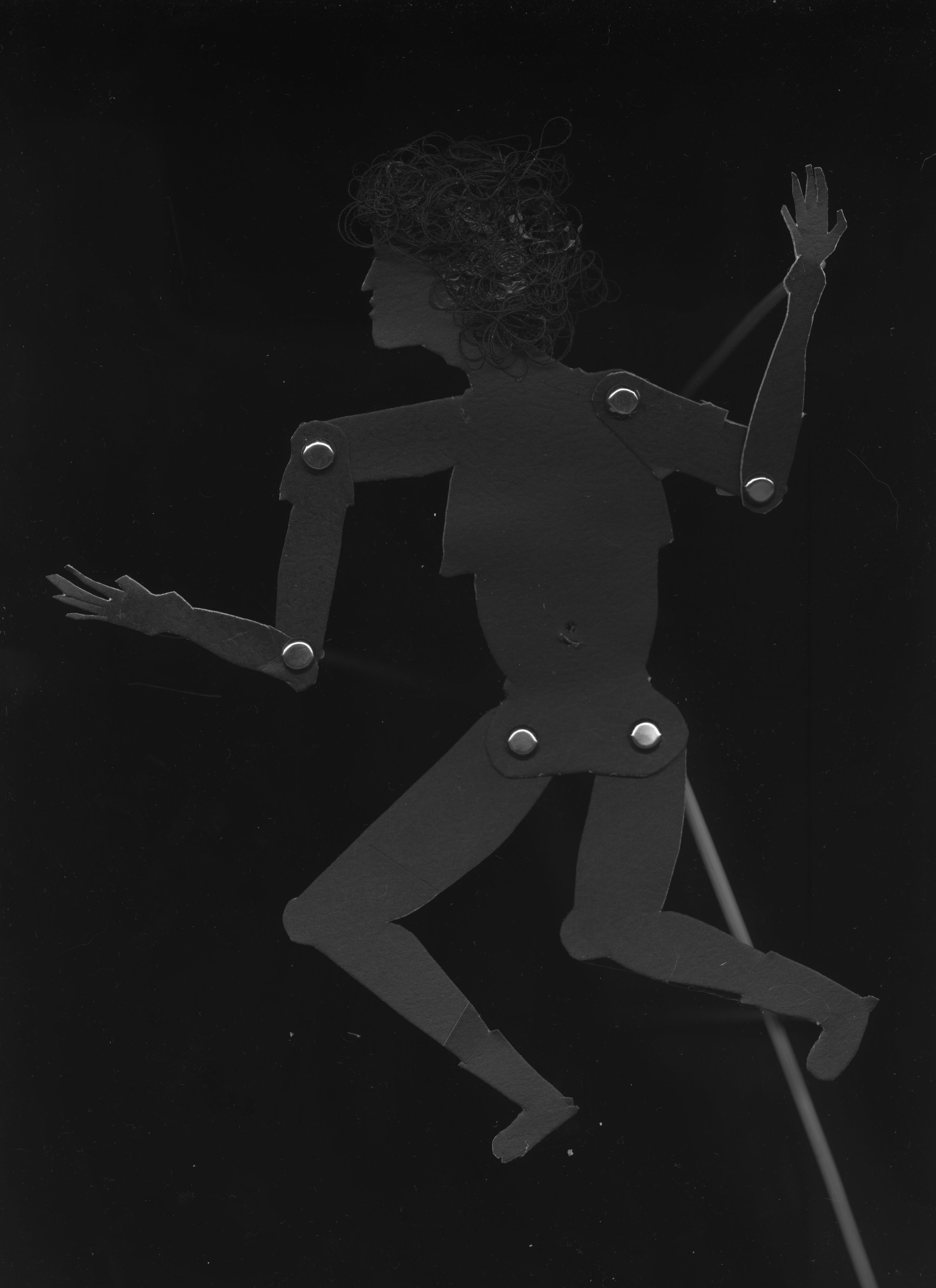

In the summer of 2023, the house held a puppet show.

The show told the story of a community house facing an eviction, and the puppets’ schemes to raise $15 million to purchase the house.

The schemes do not go according to plan.

I can confidently say if Ag Lago was was having a party…Other places in town, maybe like… shouldn't.

We always have a really weird theme and I feel like over the years the themes have just been getting more and more ridiculous.

It's really fun, like the whole space transforms. Future disco, bikini beach party from outer space.

They start late, they go late. Librarians versus barbarians.

A lot of the parties are actually really blurry for me. Ummm. Let's see… God versus science fair.

Our Vegas party was a lot of fun. Viva Log Vegas.

Our house, it usually is really well known for it's New Year's parties.

There was one year where we had no New Year's Party and a person or two still showed up because they just expected an Ag Lago New Year's Eve to happen.It's the place to be on New Year's

The fall of the holy ramen empire

Can you explain what the theme, what that one was?

Um, well,… that one was just like Holy Roman Empire, but Ramen. It's in the name. I dunno what else you want me to say.

To me, it seems like they knew that this building was an RSO and part of their strategy for dealing with this building and the tenants in it was to never acknowledge the fact that it was under the rent stabilization ordinance. Like that was part of their strategy.

Our house for years was registered as a boarding house, and so we assumed that we would be protected under the RSO 'cause that protects multi-family residences. And we learned that they pulled a sneaky trick on our last lease and snuck the language single family in there. So it kind of roped us out of a lot of our rights to be evicted individually and receive separate payouts to leave.

That's kind of where the first initial investigation was, which is are we protected under the rent stabilization ordinance or not? And if they somehow stripped us of that protection, can we prove that they did that? We dug through pieces of microfiche dating back to 1974.

And so we looked it up and use code 008* is a boarding house. And so like in the library we got super excited and high fived and you know, we're like, we found the information that we needed, which was exhilarating. *(correction: boarding house use code: 0800, single family home 0100)

We ultimately find that the courts are not that clear cut and that still requires a lot of argumentation.

Well, six people are represented by one lawyer. I'm represented by another lawyer, and three people are self-represented.

The first time we went to court under the advice of the tenants union, we had like a number of our friends join us in red t-shirts to show support.We asked friends and community to come and so many people showed up that the clerk…kicked everyone out of the courtroom

This is my first time seeing housing court play out and like, I guess I didn't have a ton of hope…

So you're just literally seeing just a lot of people get evicted every day.

Every time we go to court, the theater and the tragedy and the rigamarole of every day in that court system is so sad and so depressing, and I just kind of try and imagine like how as the species that we are and the rareness of this time that we have, that we've gotten to this place where eviction court is a large part of many people's lives… It's so stupid.

Draft letter for approval, Silver Lake Neighborhood Council (Pg 1)

Draft letter for approval, Silver Lake Neighborhood Council (Pg 2)

“Not only is it one of the rare, affordable housing spaces in this whole neighborhood and city, but it's this beautiful textured community of people that will disperse after this, separate from each other—forever. And I think it also will mark a real end of an era of, you know, the rapid gentrification of cities and the rising rent prices and the aging of houses like this that aren't built anymore. It feels like the end of an era in a bigger way than just this house — ”

This is an audio-first story. For the full story, including the puppet show, make sure to listen to the podcast episode.

This is an audio-first story. For the full story, including the puppet show, make sure to listen to the podcast episode.

Thanks:

Revé, Jeremy, Vita, Josh, Donnie, Storai, Theo, Arden, Sarah and Eleanor.

+ Emily, Spoorthi, Greyson

+ the countless folks that were part of the Ag Lago community.

Chapter markers by Cal Bannerman of the podcast Stories from The Hearth.

• Music • Timex - pAS dOO • Deville - Yclept Insan • Auld Lang Syne • Marionette •

Tags, Topics and Mentions: Ag Lago, Silver Lake, Los Angeles, New Years, New Years Party, LA, Sunset Boulevard, Sunset Junction, Santa Monica and Sunset, Eviction, Demolition, Puppet Show, Eviction Puppet Show, A Different Light, Housing Court, RSO, Food Not Bombs, LA Tenants Union, Silver Lake Neighborhood Council, What to do when you see a demolition notice on your house, punk house, community house, bicyclesOrganist Edward Torres at the Bob Baker Marionette Theater

Up the freeway a few miles from Downtown Los Angeles, the streetlights flicker on as I approach the warm glow of the Bob Baker Marionette Theater. Inside, I meet organist Edward Torres.

What was once a silent movie house, long ago, now buzzes with the sound of children, their parents, and a handful of chatty 20 somethings who are neither.

This is the Bob Baker Marionette Theater, and through the swinging doors from the lobby, a bright red carpet unfurls down a gentle slope, all the way to the bright red stage curtain.

To the left of the stage, still a few minutes from showtime, another red curtain has been pulled to the ceiling, and in a raised alcove, the back of an ornate jacket faces the audience, light glints off the shining sequence.

The person wearing this jacket is almost entirely enveloped by a cockpit of levers, foot pedals, buttons and 4 rows of piano keys. His fingers glide across all of these options with amazing fluidity.

This is Edward Torres, the organist at the puppet theater, and he weaves through a medley of arrangements like a driver dipping seamlessly from lane to lane, each song a passing exit or town.

“At an early age I discovered that I could play my emotions through my fingers... performing on this particular instrument for me, is an extremely personal zen, if you will.” - Edward Torres

Bob Baker Marionette Theater does puppet shows in cabaret style, which means the puppeteers are fully visible during the performance. For most of the shows they wear a striking all-red outfit which blends into the theater’s backdrop but you can see them the whole time on the strings. The stage is lower than the seats, on a gentle slope, and the puppeteers don’t act or provide vocal accompaniment. Instead, a prerecorded track of layered audio plays through the house speakers featuring voice actors, sound effects and vintage show tunes, to which the puppets sing along and perform intricate choreographies. It’s hard to describe the form, but the effect is an arresting cascade of expressive, blinking works of hand-crafted art. The audio tracks are a work of art too, many assembled by Bob Baker himself, splicing together physical tape from a deep archive reaching well into broadway and hollywood history.

“…it’s getting back to basic human interaction. And the overall feeling of being a part of something. Truly. It's beautiful, I think. But anyways, I just play the organ, I don't know!” -Edward Torres

The Bob Baker Marionette Theater was founded in 1963 — Bob Baker had been creating puppets since childhood, and he founded a physical theater on the edge of Downtown los Angeles, which ran shows and enchanted children for 50 years in that location. After Baker’s passing in 2014, the theater fell on tenuous times, and they were pushed out of the building that the organization, and it’s collection of thousands of puppets had called home for decades. The building was slated for redevelopment, but still sits vacant. They were able to find this building, what was once the York Theater, a silent movie house in highland park, and had been a whole string of things including a church in the mean time. It transformed into a dreamy, whimsical space, complete with a theater organ.

The move to this new space was in 2019, and just 4 months after it opened, the pandemic hit, again threatening the theater’s survival. But, they pulled through, and returned post-pandemic with a show called Reopening Revelry.

The Bob Baker Marionette Theater, interior.

An oil derrick and mountain lion puppet hang dormant backstage after the show.

“…in terms of theater organs, I think that they will survive and thrive in the new world setting not just as being a solo instrument, but as being a part of something else. I think that's their best bet to survive in this world.” -Edward Torres

“Audio is not a technology, but a process that employs technology to construct temporary social architecture made of air.” - Micah Silver, Figures in Air

Tags, Topics and Mentions: Edward Torres, Ed Torres, Bob Baker Marionette Theater, Theater Organ, Organist, Puppets, Puppetry, Puppet Theater, Puppet Theater Los Angeles, LA, California, Figures in Air, The Wind, Organ, Silent Movies, Silent Movie Theater LA, Highland Park, York blvd, Freeway, Western Tanager, Mockingbird Car Alarm, Historic Theater, Organs, Historic Organs, Edward Torres OrganistHenry Real Bird at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering

Off the train in Elko, Nevada we meet cowboy poet Henry Real Bird, former Montana Poet Laureate, teacher and bronc rider from the banks of the Little Bighorn.

Cowboy poetry is often very structured. The good poets play with that structure and surprise you with twists or a pauses, jokes, word play. Henry’s poems do somethin’ else entirely. They feel like suddenly you’re walking down a path and you don’t know where it’s goin’, or if it’s goin’ anywhere, but it usually does and then you’re somewhere a little different and he says thanks and puts his hat back on and sits down in a chair at the back the stage.

Portrait at the Gathering by Kevin Martini-Fuller

“Where am I from? Yeah, I'm from Garryowen, Montana, and that's the Crow Indian Reservation. And that's on the Little Bighorn. And I grew up there pretty much speaking Crow Indian until I was maybe five, six years old. …I grew up, strong, and, now, now that I'm writing more about my life, I see how lucky I am. I was a strong person. I rode bucking horses and then taught and put together a ranch and stuff like that against the odds. Yeah. Okay. Yeah. What else?’’

The National Cowboy Poetry Gathering started in 1985, becoming an annual roundup of cowboys, ranchers, poets, artists and the many combinations therein, hailing from all parts the American west and sometimes beyond. Hosted by the Western Folklife Center, the gathering is always held in January/February when folks’ ranches are dormant. Elko’s oft-snowy streets are then marked by the soles of boots, mostly of the cowboy variety, some rounded, some pointed, and most of them pointing into the Western Folklife Center’s Pioneer Saloon, or up the front steps of the Elko Convention Center.

Featuring:

Henry Real Bird | Library of Congress Recording

The National Cowboy Poetry Gathering | Western Folklife Center

Mentioned in the interview: Andy Hedges’ podcast interview with Henry on Cowboy Crossroads. This is a great podcast if you’d like to dig deeper into cowboy poetry.

All year, the words come up from the land itself

and the poets bring them to town.

we all feast

and we leave warm and full, or cold and spent or some combination and the snow falls starting at dusk and then on through the night

Then the wheels rumble beneath us, “tomorrow is only a horizon

It’s the line wavering under my feet” -[M Jiang]

and behind, Elko as a tiny speck,

buzzes away

over the horizon.

Tags, Topics and Mentions: Henry Real Bird, National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, Western Folklife Center, Elko Nevada, Garryowen Montana, Crow Indian Reservation, Little Bighorn, Cowboy Poetry, lullabies, poetry, western poetry, Thought by henry real bird, cowboy crossroads podcast, the wind podcast, rural art, rural poetry, american west