An audio investigation of Reno’s whip culture.

How a small sonic boom came to represent homelessness in Reno, and how the city responded to unhoused people taking up sonic real-estate.

Utility, aesthetic language, 911 tape and the search for Reno’s master whip maker.

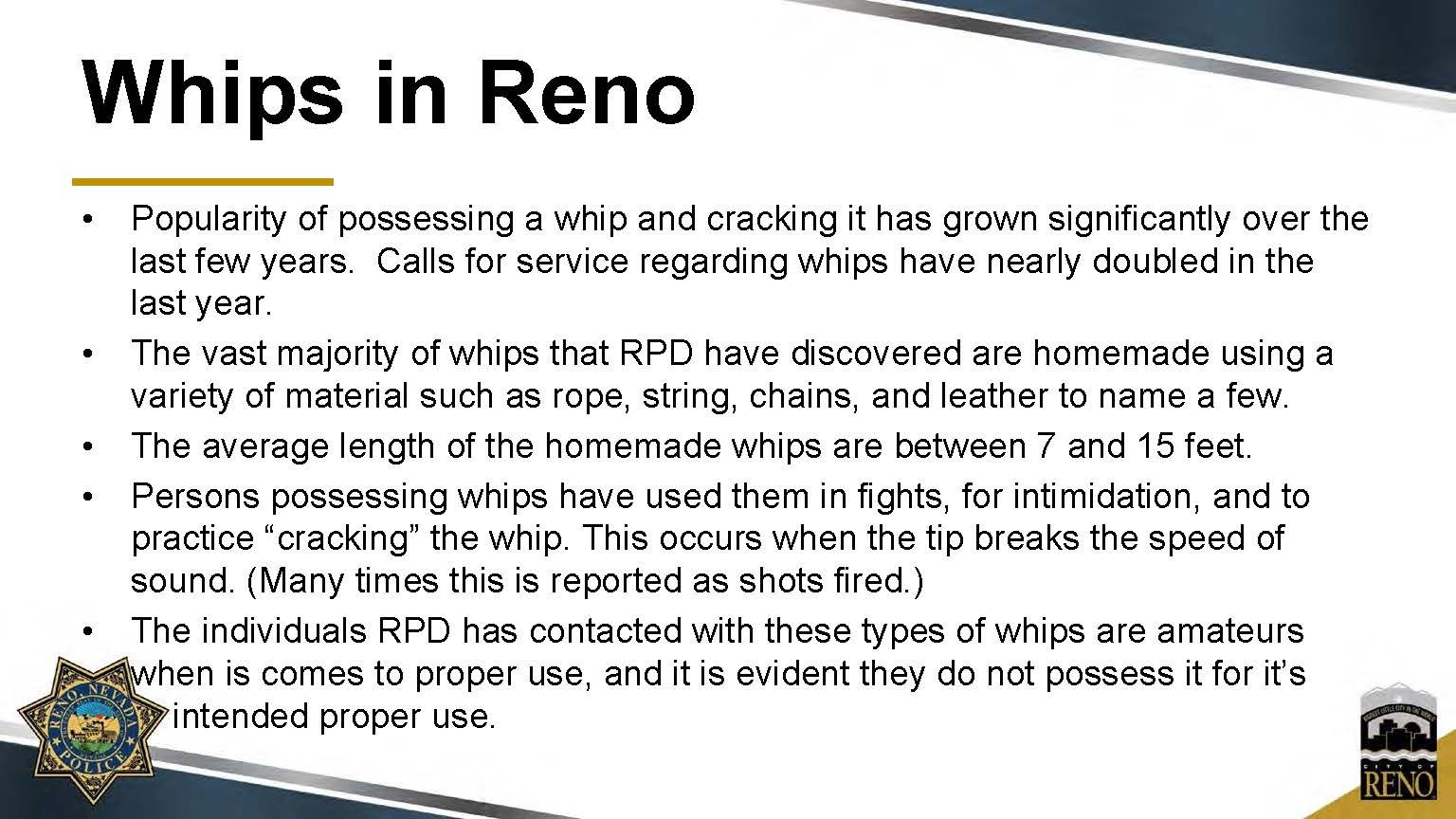

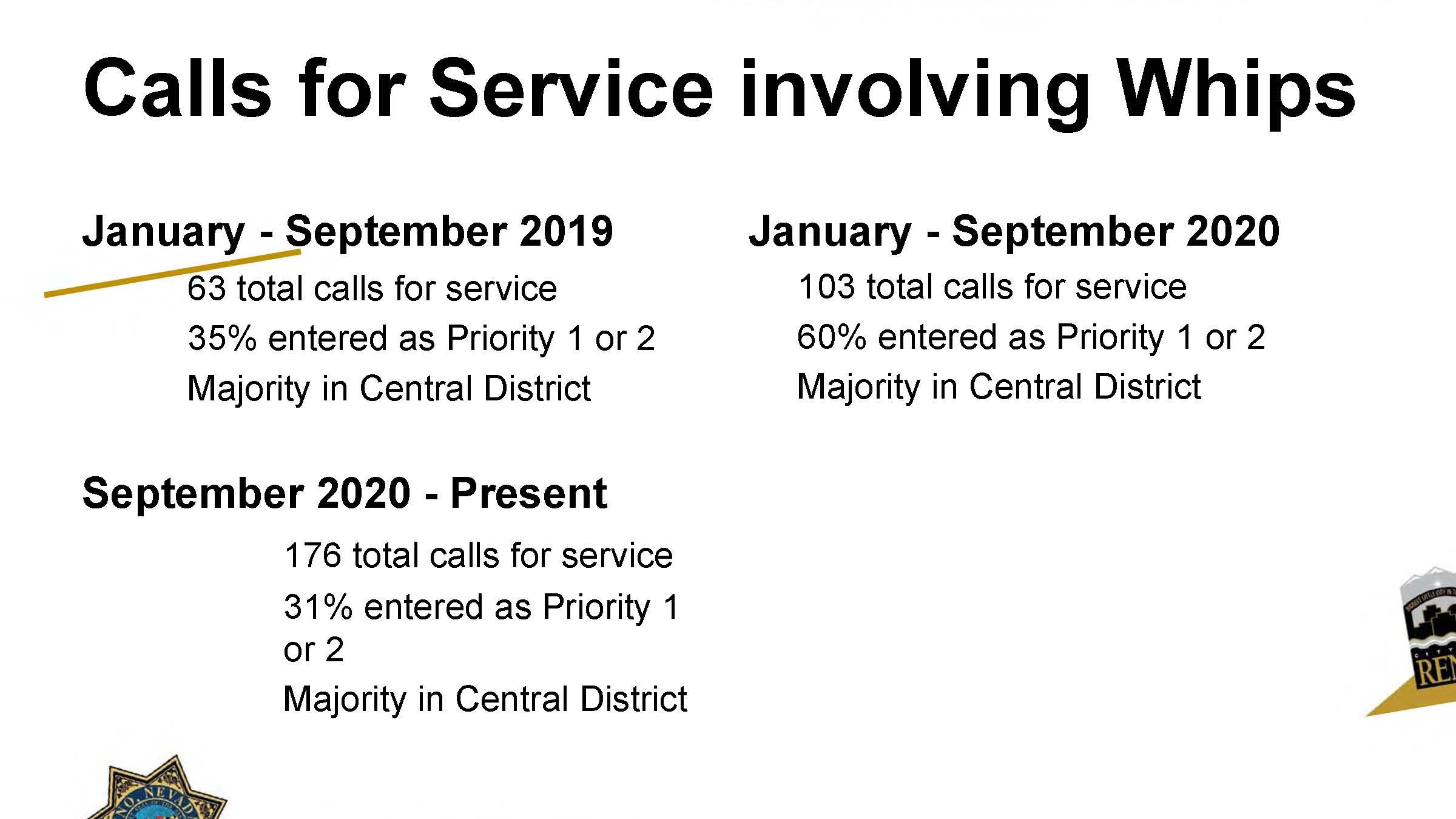

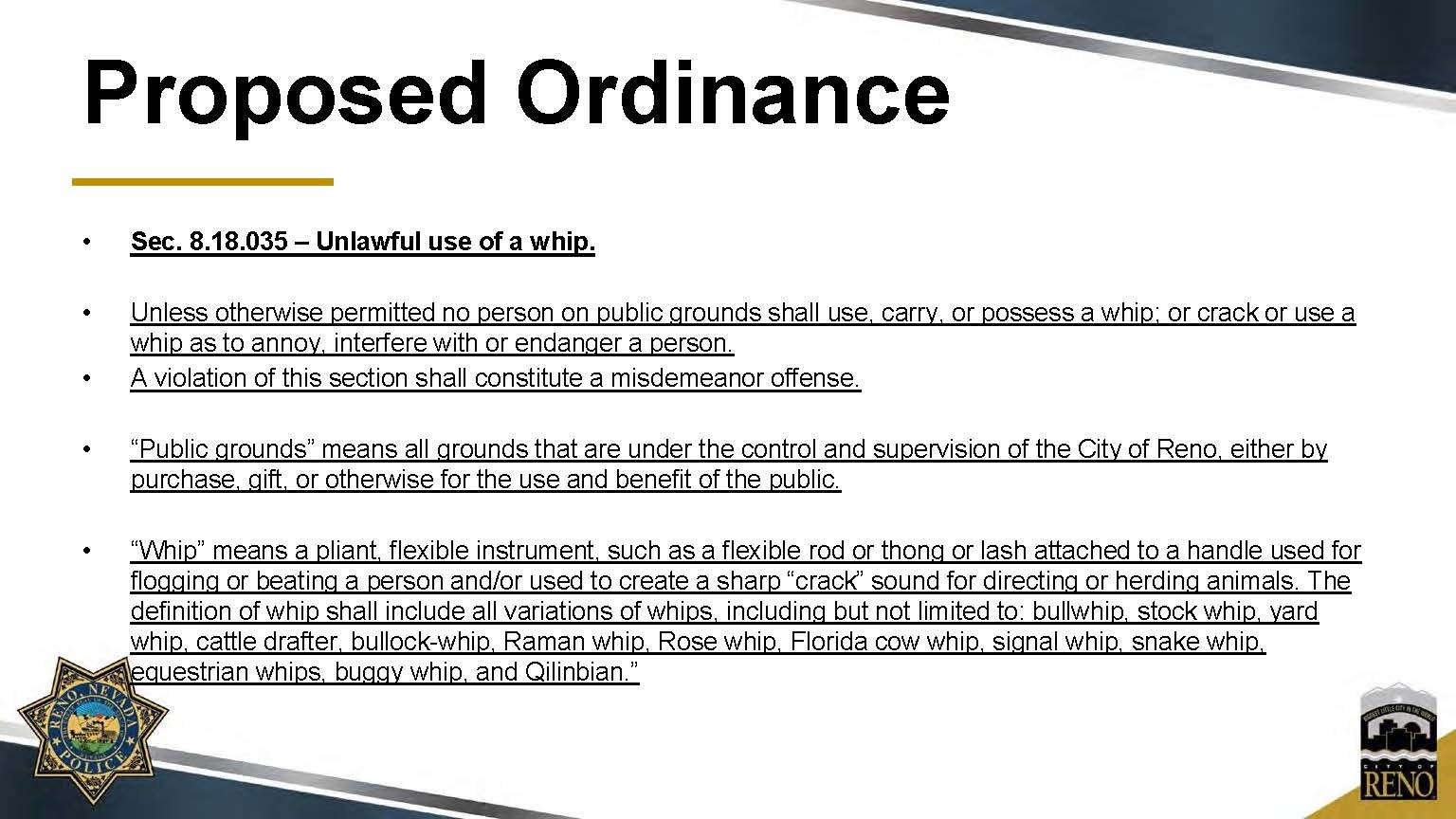

“The popularity of possessing a whip and cracking has grown significantly over the last few years…Calls for service regarding the whips have nearly doubled over the last year.” - Lt. Ryan Connelly, Reno Police Department speaking to city council.

“…we gotta travel at night. We don’t want all of our stuff out here. So we travel the bike trail. And there’s skunks and raccoons and even snakes, gosh you name it. Well we had a bear down here, know what I’m saying? So that crack is very useful to make em go away for sure.” - Monica Plumber

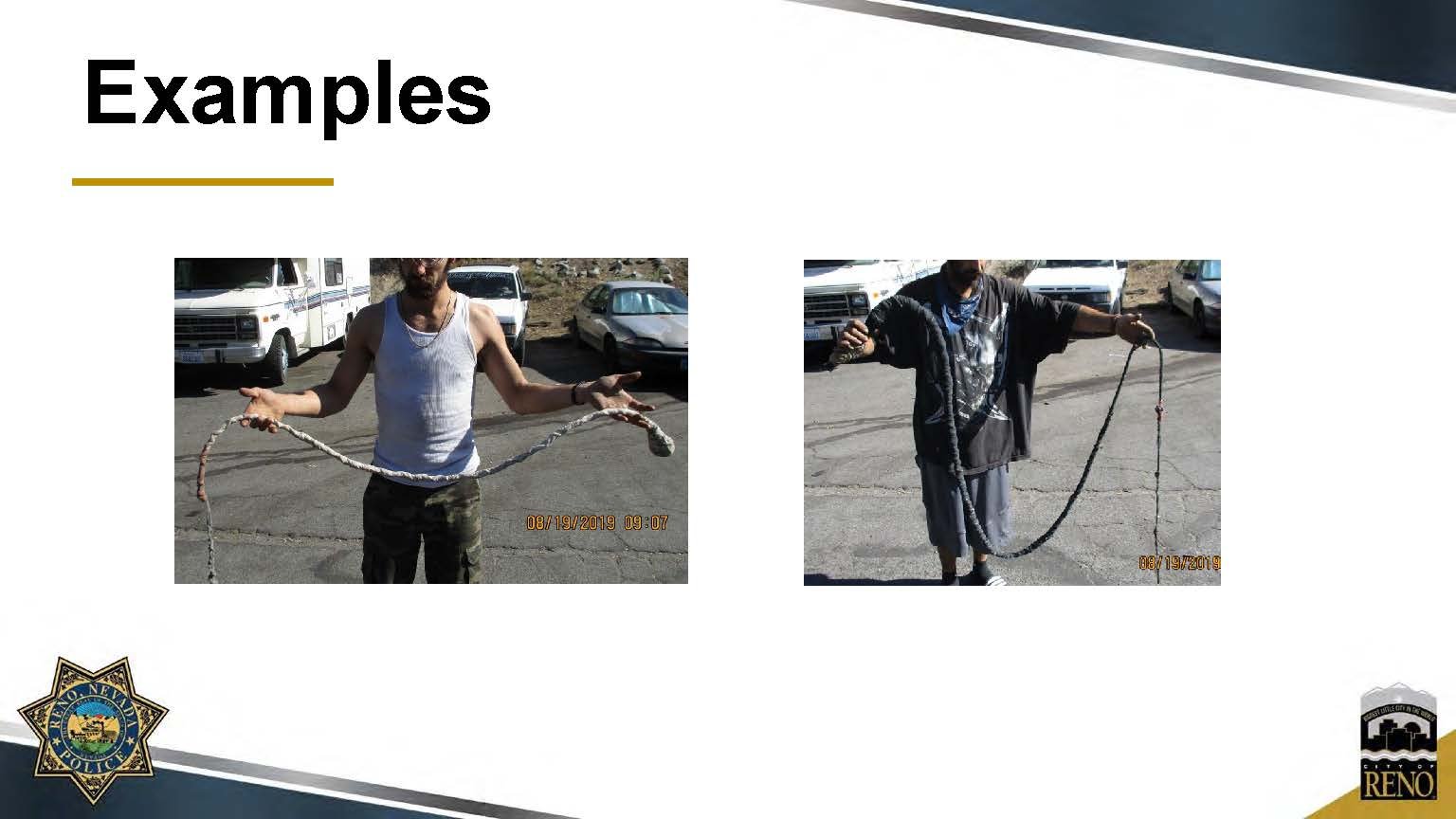

“The tip of the whip obviously breaks the sound barrier, if used correctly, the integrity of the whip is compromised, due to not being professionally constructed and the materials that they are made out of…..The vast majority of the whips that we have seen in and around town are homemade, and they use a variety of materials such as rope, string chains, leather to name a few.” - Lt. Ryan Connelly, Reno Police Department

“And you know, one has a different sound than the other. We can tell who’s who just from the crack from down the river. It’s amazing... You can really tell where your family is at…” - Monica Plumber

“I ask that you pass the proposed ordinance regarding whips. I frequently hear the whips cracking. I hear them from my home. I hear them when I'm out and about. They make a very scary noise. They basically sound like a gunshots…” Eric Lerude, Public Comment

“…I enjoy the public spaces and the last couple of years, it gets worse and worse. Three a.m. in the morning, it's simulated gunfire. And it's a means of intimidation...” Anthony Townsend, Public Comment

“…I think that the whip ban is discriminatory. … I mean, if there's if there's an issue of them attacking people with the whips, that should be a an assault thing. And there's already laws in place for that… Why are we making criminals out of people over something that helps them?” Gabe Stransky, Public Comment

“The unsheltered population is over-policed, lacks trust in law enforcement, and this ordinance threatens any efforts to build that trust…” - Holly Wellborn (ACLU of Nevada), Public Comment

“I don't believe that artistic expression should interfere with people's quiet enjoyment of their property.” - Councilmember Naomi Duerr

“…I think it's intimidating. I think it's absolutely dangerous….This is in no way an art form, I'm sorry…” Reno Mayor Hillary Scheive

“I've heard from the people for this ordinance and people with concerns for this ordinance that they understand the whip crackers to be people who are homeless. Is that like a universal given as we move forward with this?” Councilmember Jenny Brekhus

“…I’m alone. I don’t have boyfriend or any of that… I don’t carry a knife…So it’s nice to know that my family is out here with me. And if I crack my whip, somebody will crack theirs.” - Monica Plumber

Monica Plumber: This is rough. This is really rough. And it’s really scary sometimes.The Wind: What do you mean by "this"?Monica Plumber: Being out here. Homeless.“Mine’s just to get attention from like everybody around, they know I'm in the area when I crack my whip.” - Hatchet

The Wind: Do you think it's about power or control?Hatchet: It's more like releasing… Because when I get angry, when I get sad or something, I just pick up a whip, it helps me release it... Honestly, I use to get physical. With people and stuff when I get angry, but not anymore. Once I started doing the whip, cracking the whip, It just released all that.”The Wind: Do you have a favorite in town?Hatchet: My favorite has to be Fernando. He braids the best.“With a lot of uses with the whip, they're using just the sound of it. (Historically) there would be different patterns or different sequences usually referred to as a flash. There would be the Queensland Flash or the Sydney Flash, and it would be basically a unique sequence of cracks or unique rhythm that would be recognizable. So you would hear that and be like, Oh, that's you know, this delivery company or, you know, what have you that's coming down the road. …” - Matt Franta, Los Angeles Whip Artists

“…I’ve been on the streets since I've been to Reno, so I've been in Reno for 14 years…I got into it because I was homeless…. At first I didn't like it. It was like, “These are stupid you guys are you're wasting your time.” But then I was like, man, “if you guys can make it, I bet I can make a better one.” Competition…I have ADHD. So my hands are always moving, and this right here, constantly, you're moving up and down.” - Nando, Downtown Reno Whip Maker

“Hello this is Lisa, a local resident of Reno, and I'm very concerned about the current atmosphere and the knee jerk reactions going on with these horse whips. It's called a crop. They are used for the hind quarter of the horse to move the horse out of tough situations such as the river, any kind of running water… So to just suddenly ban them. It's it's silly. Being a horse rider and knowing many ranchers here in town, we're just appalled. I can't believe this. Please reconsider the decision because valuable tools and can often be used to help move the horse in a dangerous situation… I cannot stress to you guys the value and the importance of retaining the horse crop for use in public service. Thank you.“ - Lisa, Public Comment

“…If you've got a horse and you're down south, that's totally fine and fair and you're not going to be penalized for using that whip. So again, it really gets to… the problem is the downtown. The problem is we have, you know, whips cracking downtown, sounds like gunshots. People report gunshots and that activity has got to stop and we don't expect to see that outside of the downtown corridor area.” Jonathan Shipman, Assistant City Attorney

“…A lot of us, we live downtown. I mean, homeless, you know, I mean, like, we live downtown and it is what it is. We don't really we don't have the means to go all the way up to the country and all that.” - Nando

“…like any sort of kind of like spiritual practice or, you know, trying to to cultivate mindfulness or meditation as as a movement artist, I prefer moving meditation, right? Something that I can connect body and mind that way rather than sitting still… it's something that you can stick with your entire life. There's always more to learn.” - Matt Franta, Los Angeles Whip Artists

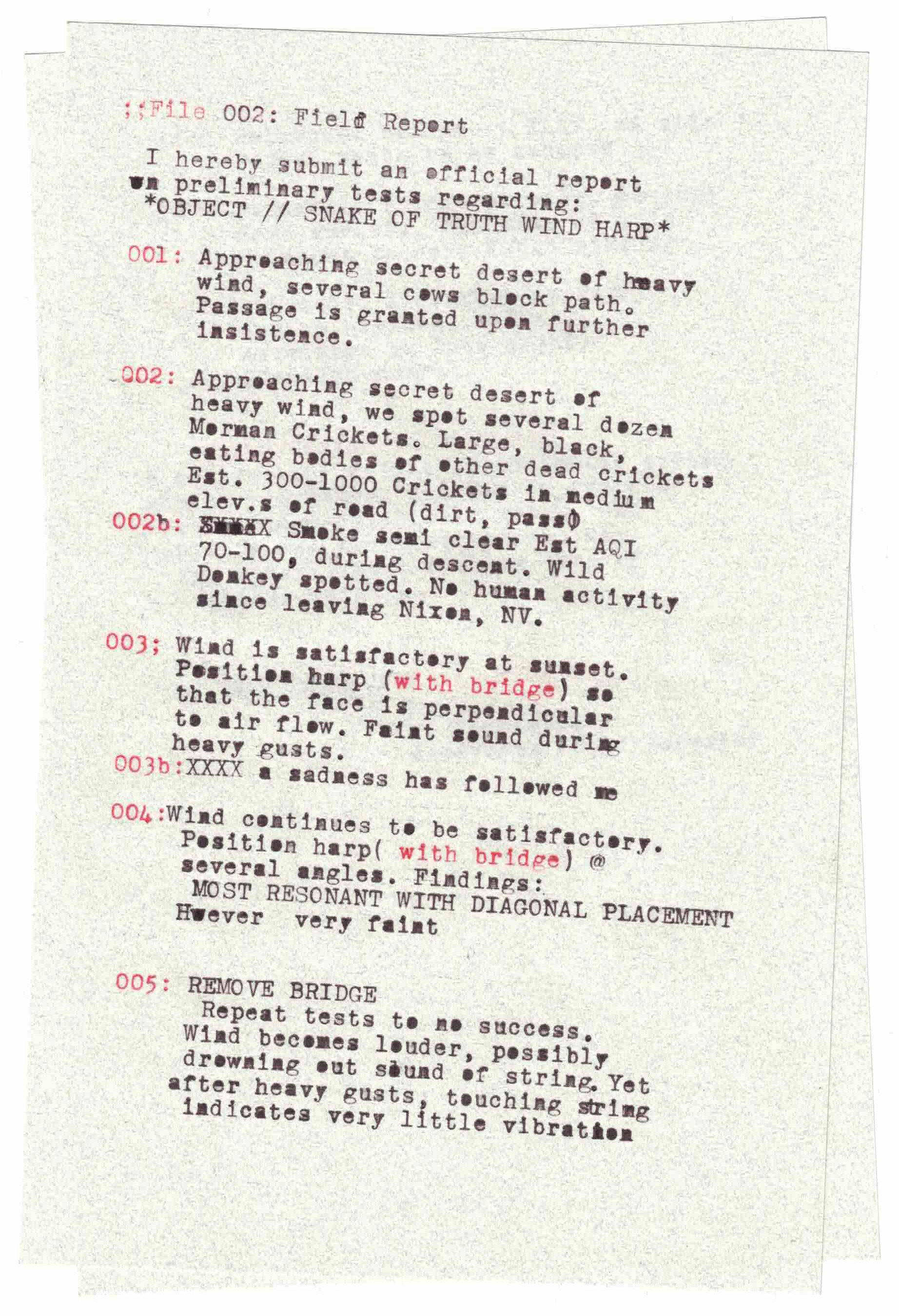

Whip. At my request, Nando braided a twig of aspen from Throat Forest into the handle. (Pictured on my desk)

“Each time I make a whip, I lose a piece of my soul. Not for the bad… Like when I do go one day, if my whips are still around, if they're not in the garbage, I'm still going to be here… this one right here, when you take this one, when I'm done with it, my spirit is in this. A piece of my soul goes, know what I mean? And … I grow a new soul. All the time I've had on the streets and all that, just everything I've been through… all the bad. It gets put into these whips, you know? I become a new me each time.” - Nando

Thank you to Emily Pratt Mike Corbitt and Anjeanette Damon for support and advice on this episode. Additional thanks to Nico Colombant & Natalie Handler. About a month after our interview, Nando was evicted from his motel room, along with everybody who lived in the building. He and his wife found another place. After the whip ban passed, I heard from a few people that their whips had been confiscated. Three people I spoke to said that they were simply making replacements, and whipping more frequently in the middle of the night to avoid detection.

Episode scored by Howls Road

+ Mountains by Yclept Insan

Math behind Whip Cracking

Our Town Reno blurb on Paul Espinoza

Matt Franta • Website • LA Whip Artists

Transcript of this story

Tags, Topics and Mentions: Whips, Reno whips, Reno whip man, Reno, Downtown Reno, Audio Journalism, Radio Journalism, bullwhip, bullwhips, reno whip law, reno whip ordinance, reno's whip problem, whips in Reno, whip culture, 911 audio, sonic booms, public comment, community journalism, Reno City Council, Naomi Duerr, Jenny Brekhus, Hillary Schieve, Devon Reese, Oscar Delgado, Bonnie Weber, Neoma Jardon, City Attorney Karl Hall, Assistant City Attorney Jonathan Shipman, Ryan Connelly, Reno Police Department, Reno Police, Reno 911, whip braiding, whip making, how to make a whip, paracord, how to make a nylon whip, whip sound, houselessness, homelessness in Reno, unsheltered population in Reno, point-in-time count Reno, Truckee River, Brick Park Reno, Methodist Church Reno, Reno City Plaza, Wells Overpass, Brodhead park, Wingfield Park, Arlington Tower, Park Tower, Reno riverwalk, Los Angeles Whip Artists, Howls Road, The Wind, The Wind Podcast, thewind.org